I spent Saturday evening at home here by the Potomac River in Virginia writing this posting, instead of attending the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, one of the big social galas, also known as ‘Nerd Prom,’ in our nation’s capital.

For decades the dinner was a chic event – a sort of Oscars East, attended by U.S. presidents who allowed themselves to be lightly roasted by comedians in front of 2,000 elite attendees and the C-SPAN audiences at home. Presidents also would turn the table on some in the audience as notably occurred at the 2011 dinner when Barack Obama ribbed Donald Trump.

Obama was serving Trump his just desserts as the New York real estate investor had been the biggest amplifier of the ‘birther’ conspiracy that the native of Hawaii had been born in Kenya, thus making the president ineligible for the office he held.

“Now I know that he’s taken some flak lately. But no one is happier — no one is prouder — to put this birth certificate matter to rest than The Donald,” Obama said at the dinner. “And that’s because he can finally get back to focusing on the issues that matter: Like, did we fake the moon landing? What really happened in Roswell? And where are Biggie and Tupac?”

The audience roared and Trump, who has also been better at dishing it out than taking barbs, grimaced. It is widely believed the ridicule spurred him to his successful run for president five years later.

Trump is the only president since the tradition began in 1921 to have never attended the WHDC as the commander-in-chief. Trump today did fly back on Air Force One from Pope Francis’ funeral in time for tonight’s dinner, but he had turned down the invitation well before the pontiff died.

My absence this year was admittedly more a value proposition than optics – it’s an out-of-pocket expense for me (unlike many journalists whose organizations foot the bill). Without a president or a comedian in attendance it literally did not seem worth it as this formal night out on the town (ticket plus hotel plus overnight parking) would have set me back more than $600. I decided to make donations today to other journalism-related causes, including the USAGM Employee Association campaign to aid the most vulnerable of my colleagues from VOA, RFE/RL, RFA and MBN who face deportation or other hardships as a result of the forced shutdown of nearly all U.S. international broadcasting.

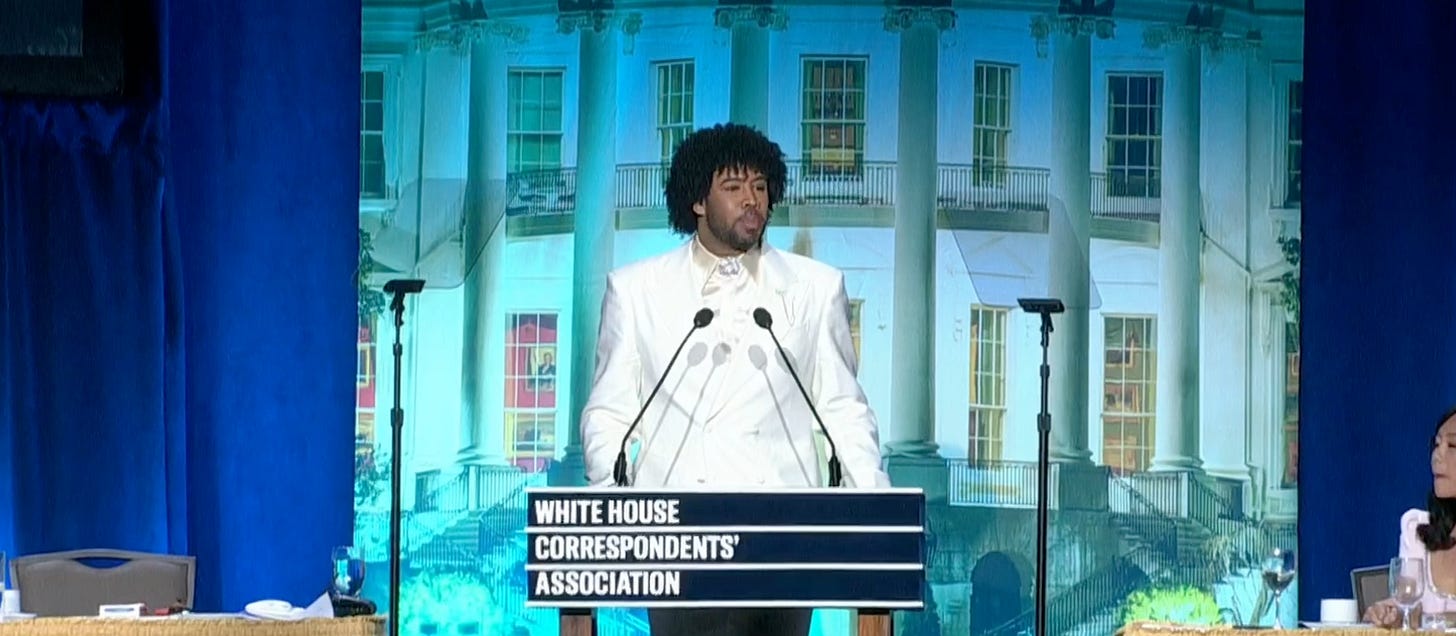

At Saturday night’s WHCD dinner, the silencing of the Voice of America was noted by White House Correspondents’ Association President Eugene Daniels of MSNBC.

Addressing the association’s VOA correspondents, Daniels said: “I cannot wait until you’re back at the White House to report important stories to audiences around the world.”

Earlier Saturday, I attended the 3rd annual AAPI White House Correspondents Brunch (dress code: garden party chic) where there was Asian cuisine undisputedly superior to the Hilton’s banquet food. (Shoutouts to: The Fried Rice Collective, Mrs. Bakewell’s, BŌKEN Sake, Party Of Popcorn, Pricklee, Sanzo, Trăm Phần Trăm, and Yoju.)

The brunch, as is the case with the WHCD, is designed as a fundraiser for scholarships, and one of the sponsors is another organization of which I’ve been a member for decades: The Asian American Journalists Association.

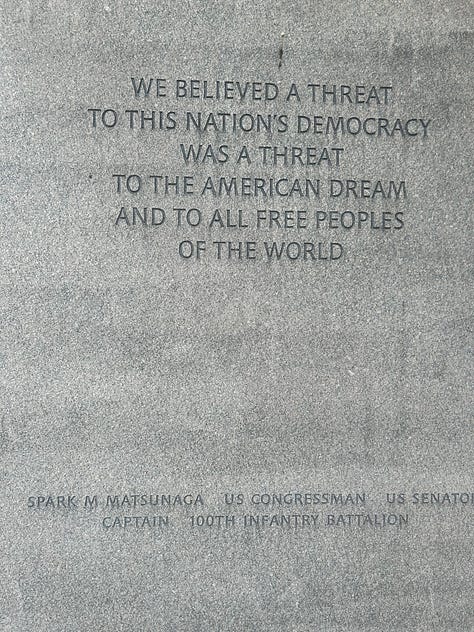

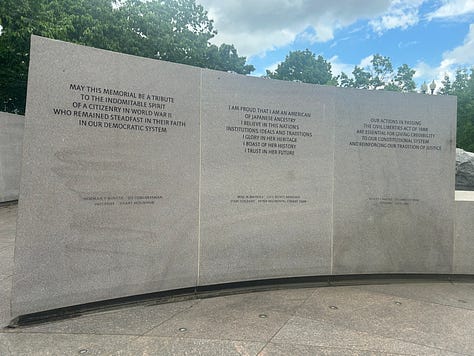

After the brunch, as a light drizzle began, I walked a couple of blocks for reflection at an obscure but important Washington landmark, The National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II (it’s located near the Capitol at the intersection of New Jersey Avenue, Louisiana Avenue, and D Street.)

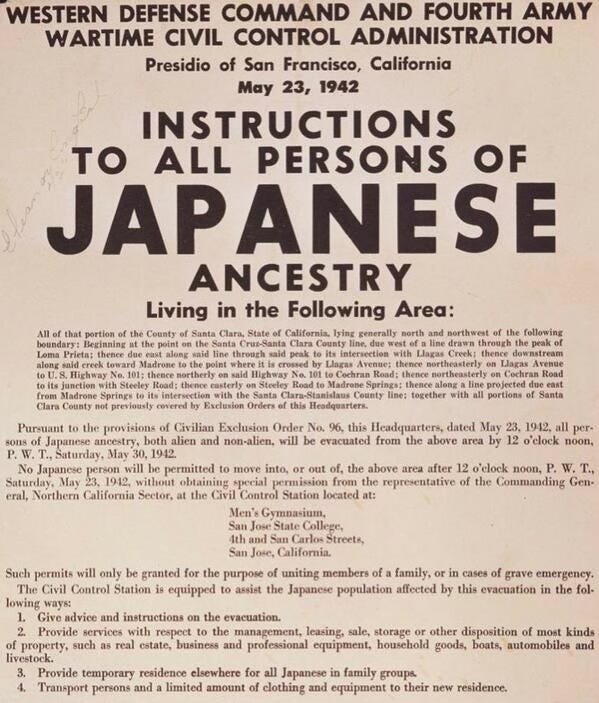

The memorial is a tribute to sacrifice, an honoring of heroism and an attempt to right a wrong. While the history is known to nearly every American of Japanese descent, it is likely a surprise to many in this country that during the Second World War our government under President Franklin D. Roosevelt forcibly relocated and incarcerated 120,000 individuals, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens. The excuse was national security. The reality was racism. The constitutional rights of men, women and children were overridden with the stroke of a pen when FDR signed Executive Order 9066.

The Alien Enemies Act, still on the books since John Adams’ presidency, grants the executive branch broad authority to detain or restrict the movements of non-citizens from nations with which the United States is at war. During World War II it was not just applied against enemy aliens but also as a legal fig leaf for the more sweeping action of putting American citizens in what were technically concentration camps. The term most infamously references the Hells on Earth to where the Nazis transported millions of Jews and other groups for extermination — either by being worked or tortured to death, starved, shot or gassed.

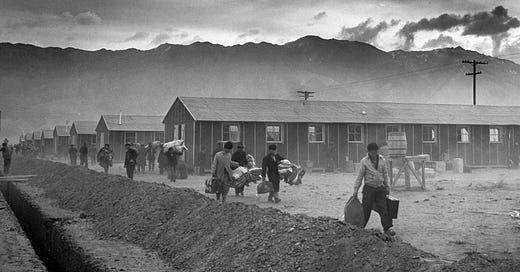

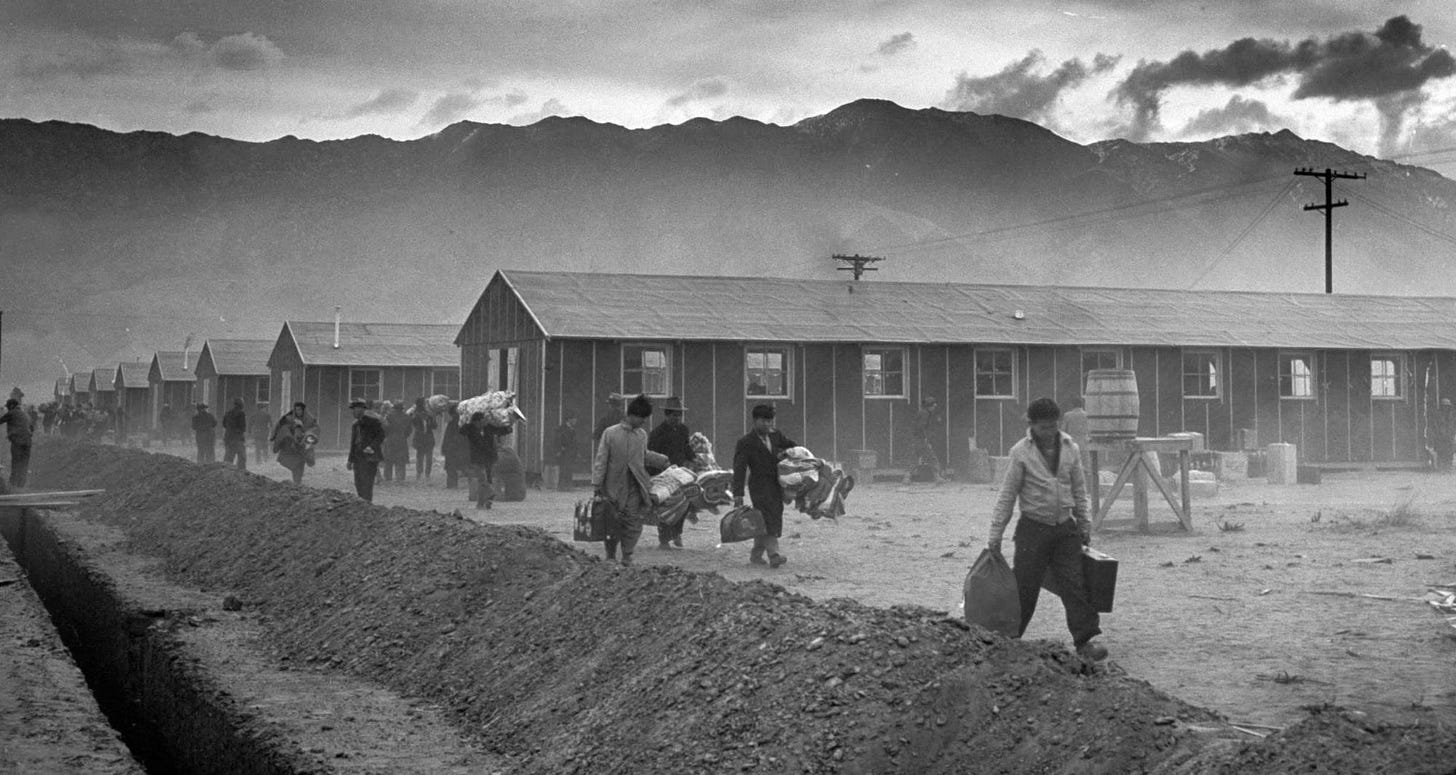

Living conditions at the ten camps for ethnic Japanese in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming were no picnic. The forcibly held, after losing their homes and most of their assets, were placed behind barbed wire in uninsulated barracks, furnished with cots and coal-burning stoves. Hot water was sparse and the internees shared communal bathrooms.

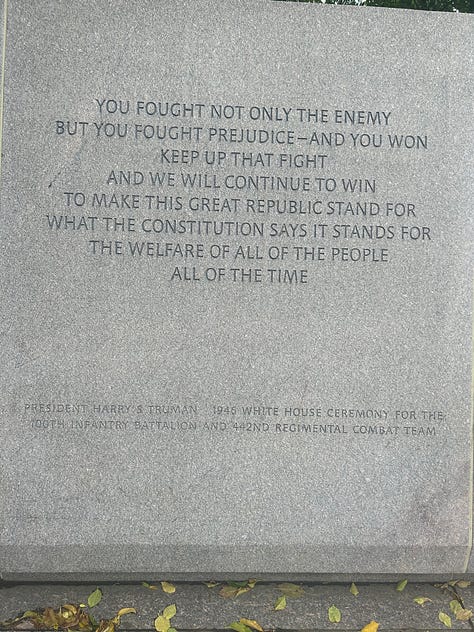

Despite the treatment, 33,000 Japanese-Americans volunteered to join the U.S. military. Their most famous unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was one of the most decorated of the war and its soldiers became legendary for the bravery. Their sacrifice served to demonstrate the depth of Japanese-American loyalty to the nation.

The Supreme Court, in 1944, (Korematsu v. U.S.) partially condemned the government’s internment program, ruling that people should have been detained only long enough to determine whether they were loyal to the United States. An official government apology would not come for another 40 years and Congress established a fund that paid some $1.6 billion in reparations to formerly interned Japanese Americans or their heirs.

As we have become acutely aware recently, the current administration has used the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 against certain immigrant populations, redefining "enemy" status based on broad or ideological criteria rather than traditional wartime definitions, re-opening a dark pathway in American governance where national security risk becomes a pretext for targeting specific groups, especially along racial, religious or political lines.

More ominous is the administration’s consideration of invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807. It was designed to allow a president to deploy military forces domestically to quell rebellion or lawlessness. But it contains language that can be broadly interpreted to deem nearly any protest movement or widespread dissent an "insurrection." Once invoked, it allows the president to bypass traditional checks and balances on domestic military deployments and law enforcement actions.

If these two statutes — the Alien Enemies Act and the Insurrection Act — are combined under this administration, the result could mirror the Japanese-American internments, but on a far wider and more dangerous scale. Certain groups, including citizen activists, lawyers and journalists could be deemed to be "enemy sympathizers" or "domestic insurgents," detained without due process, and confined in government-run facilities. This is no longer hypothetical. Discussions of concentration camps for migrants and political detainees (those deemed disloyal) circulate among Trump administration officials and in far-right social media, following the president’s threats to use the military and Department of Justice to go after those he deems disloyal.

A way-station in American history between Manzanar (1942-1945) and Bluebonnet (2025-?) came close to being established in Wyoming and other Western states.

Under the Huston Plan of the Nixon White House in 1970, thousands deemed to be “domestic security threats” were to be illegally surveilled and potentially rounded up. The long-term internment of those detained would have been authorized under what was known as the ‘Concentration Camp Law,’ formally the Internal Security Act of 1950, which Congress enacted over President Harry Truman’s veto. (The internment element stayed on the books until 1972.)

The ramifications of the Huston Plan were all too much even for FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Attorney General John Mitchell, two men who had no qualms about approving unconstitutional actions in other circumstances. Nixon, within a period of two weeks, approved and then rescinded the plan whose namesake was White House aide Tom Charles Huston. The FBI’s Mark Felt (who later unmasked himself as the ‘Deep Throat’ informant of the Watergate era), regarded Huston as the White House gauleiter.

The Huston Plan was retained as a model for subsequent illegal activities, including the break-in at the Watergate Building, leading to the political scandal and Richard Nixon’s resignation as president.