Merrifield, Virginia — At the rendezvous point in the garden center parking lot, the two precious boxes in the back of the Tesla were briefly opened for a final inspection before being swiftly placed in the Jeep. After a Zelle transfer of $100, the deal was done.

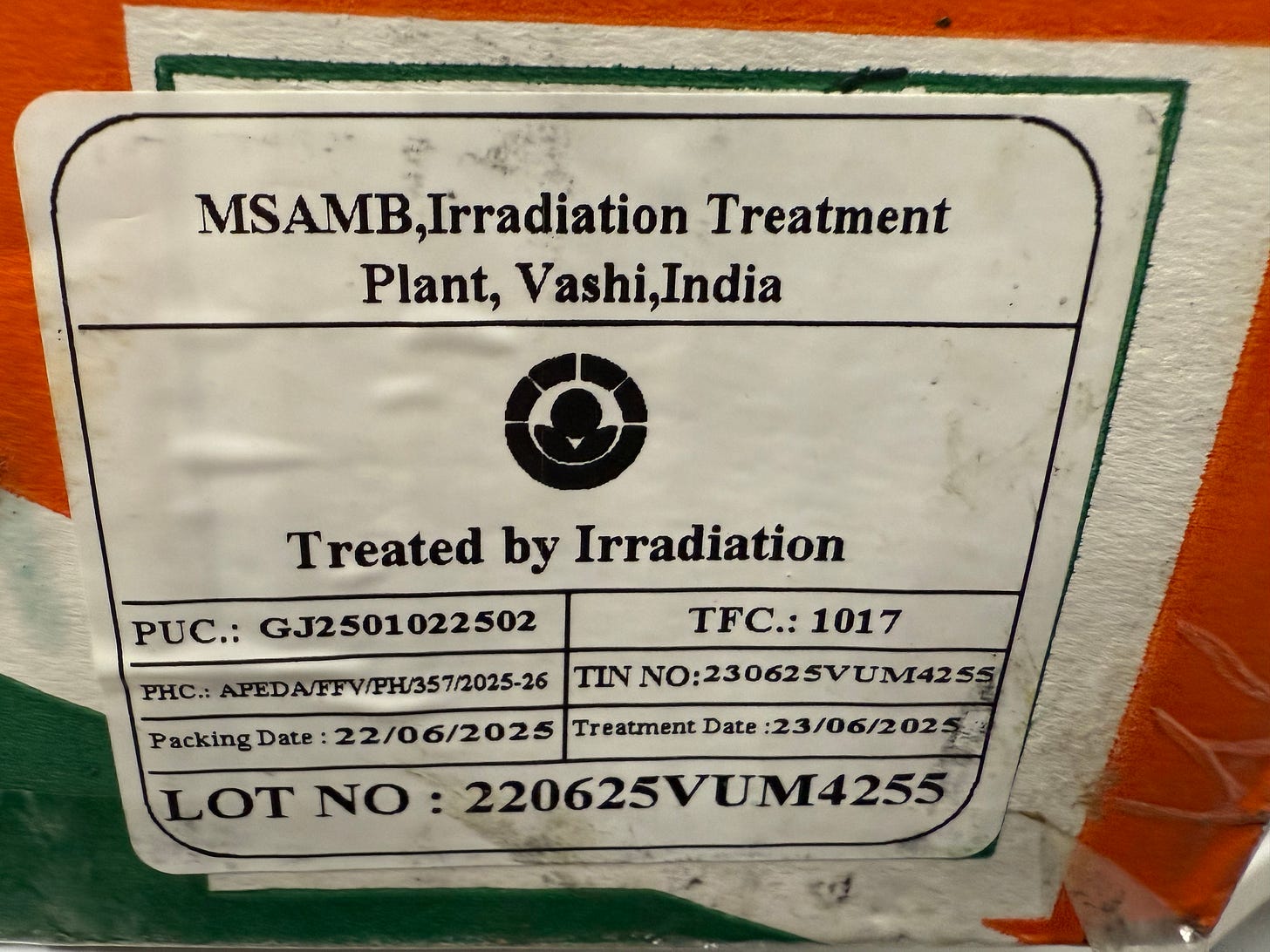

The final destination for the cargo was my home, 30 miles to the south. The cartons had been irradiated and packed in India just four days prior. Now their historic journey was complete.

Anyone in India or from India likely has figured out the mystery contents. To be specific, we had secured eight chaunsas and nine langras — in all, 17 Indian mangoes from the season’s final consignment imported to the United States.

I had been tipped off to the trade by Karan Madhok’s article in the Indian outlet The Print.

Madhok profiled a northern Virginia IT manager, JP Gola, who had accomplished what many desis in the diaspora had fantasized about for decades: biting into a slice of a just-peeled, juicy alphonso or mallika harvested days ago in Karnataka.

For anyone who grew up in India, summers means mangoes. It is the ultimate passion fruit for the denizens of South Asia. Making an analogy to Americans and their apple pies doesn’t begin to describe the depth of the relationship.

Mangoes have been cultivated on the Indian subcontinent for thousands of years. They’re practically holy — mentioned in the Hindu Vedas and associated with enlightenment and generosity in Buddhism. Mangoes are no less revered in Muslim Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Raw mangoes go into chutneys. Ripe ones are eaten plain but also end up in curries and lassis.

It is difficult to categorize consuming mangoes as a guilty pleasure because they are not only good — but so good for you.

The completely fiberless fruit is a rich source of vitamin C and antioxidants. Mangoes also are a primary dietary source of mangiferin, which reduces inflammation, and some scientific studies indicate this polyphenol may help ward off diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

In Ayurvedic medicine, mangoes aid digestion, are virya (I’ll translate that as “potent”), and enhance ojas (nourishment and satisfaction).

For those living in Kolkata or Karachi, securing the summer supply of mangoes is cheap and easy.

In America, you need to know one of the few mango importers who can navigate the regulatory and logistical hurdles. Until a few years ago, the barriers meant just a couple hundred tons per year made it to America. This fiscal year has seen at least ten times that volume. But demand here still far outweighs the supply — even if it can be more than ten times as expensive to eat an Indian mango in America as on home soil.

JP Gola communicates with his elite customers on an invitation-only WhatsApp group. I managed to track him down in the nick of time, thanks to fellow journalist Karan Madhok.

As Gola told Madhok: “Imported mangoes from India are always like a ticking time bomb.”

The fruit must survive an irradiation process in Mumbai before boarding a flight. A recent data glitch at the processing facility led to a dozen mango consignments being rejected by U.S. authorities in May.

Even compliant shipments can be lost in bureaucratic limbo due to documentation errors.

My two boxes appear to have been handled by Air India and Ethiopian Airlines before arriving at Dulles International Airport on Wednesday.

Once they are deemed to meet U.S. FDA sanitary standards and Customs regulations, Gola races to deliver the mangoes to anxious customers. Other importers fetch their mangoes at airports in Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Denver, Dallas and Newark — all hubs for significant Indian-American populations.

At 50 bucks a box, the Indian mangoes (which, subjectively, are far superior in taste to others) are not competitive. Less discerning buyers can purchase cheaper mangoes from Latin America. But anyone who has tasted an Indian mango will not be satisfied with those inferior fruits.

I have to admit, the subject of Indian mangoes was, for years, a source of irritation when I covered the White House.

The daily news briefings were a competitive sport, with dozens of correspondents vying for the press secretary’s attention.

More than once, when I had a burning question on a serious geopolitical matter, the briefer — looking to break the press corps’ momentum — would turn to a slightly disheveled man standing in the aisle, pen and pad at the ready.

Raghubir Goyal — both a legend and a gadfly — had been in that spot since the Carter administration. Press secretaries knew they could count on him to ask a question wholly unrelated to lo scandalo del momento.

Goyal the Foil, more often than not, would ask about negotiations between Washington and New Delhi regarding mango imports (which at one point were part of a proposed trade deal involving Harley-Davidson motorcycles entering India).

Goyal’s mango monologues ran out the clock, often costing me the chance to ask about U.S. relief for Burmese typhoon victims or tensions in the Balkans. It was all the more maddening since I knew — and the press secretaries knew — that Goyal was not really a reporter. He claimed to be the editor, publisher and correspondent for the India Globe. But the Globe seemed to exist only in Goyal’s mind — along with the delicious mangoes he dreamed about.

As I recalled in my book, Behind the White House Curtain: A Senior Journalist’s Story of Covering the President – and Why It Matters, I confronted Sarah Huckabee, a press secretary in the first Trump administration, about why she continued to call on Goyal over legitimate journalists.

“Oh Goyal. We’ll never get rid of Goyal — he brings us fruit,” Huckabee replied.

The current press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, should certainly be expecting at least a luscious Kesar for humoring Goyal. My only question is: now that mangoes are on the table in America, what else could he possibly ask?

I think I have an answer. Unless the United States and India reach a trade agreement by the end of July, mangoes could again be in a squeeze.

President Donald Trump today expressed hope for “a very big” trade deal with India next month. But then again — maybe not. His tone implied India must fully open its market to U.S. businesses — or else. Trump on Friday abruptly cut off trade talks with Canada over Ottawa’s pending digital tax on U.S. tech firms.

The Indian mango season is over. Whether I can afford a box or two next summer may hinge on whether the Trump-Modi relationship continues to ripen — or turns sour.

That makes the mangoes currently in my kitchen all the more savory.

Delicious writing!